Pyloric Stenosis In Babies: 6 Key Signs, Causes, And Treatments

Uncover key factors, warning signs, and care options for a common infant digestive condition.

Image: iStock

Is a baby’s crying and vomiting always dangerous? Not really. A lot of babies cry and many throw up (regurgitate) mostly from overfeeding. Lurking amidst, are some health conditions, which are really really important to know about. Pyloric Stenosis is just one of such things.

Pyloric stenosis causes severe discomfort and nasty projectile vomiting in babies. The condition eventually leads to poor appetite, dehydration, and stunted growth. Prompt intervention helps avoid these issues in an infant. So, what is pyloric stenosis in babies and what causes it? Through this post, MomJunction throws some light on this critical infantile illness.

What Is Pyloric Stenosis?

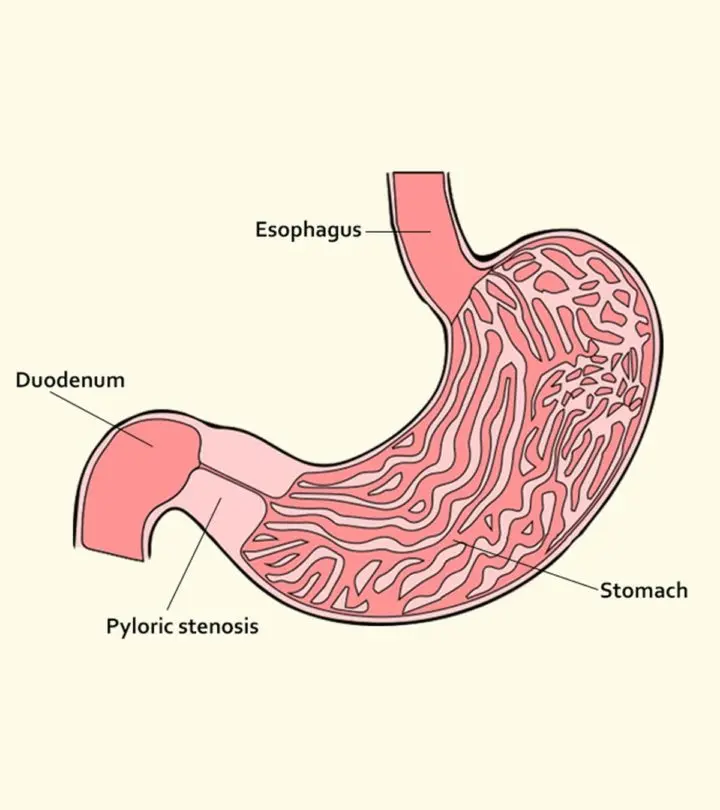

Pyloric stenosis is the thickening of the pylorus muscle present at the intersection of the stomach and the small intestine.

The pylorus plays a crucial role in regulating the outflow of stomach contents into the duodenum, which is the first section of the small intestine.

Pylorus is a thick muscle band or sphincter that opens and closes like a valve, permitting the movement of food. When the muscle thickens, it constricts and prevents the food from moving into the small intestine . The thickened sphincter and hindered food movement eventually cause pyloric stenosis . It is known by other names such as infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, pylorostenosis, pediatric pyloric stenosis, and neonatal pyloric stenosis.

As mentioned, pyloric stenosis is caused by the thickening of the pyloric muscle. But, how does the muscle thicken?

What Causes Pyloric Stenosis?

The exact reason for the thickening of the muscle is not known but it is speculated that the abrupt thickening could occur either at birth or early after birth. These conditions lead to two types of pyloric stenosis in infants:

- Congenital pyloric stenosis, also called congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, occurs when the baby has a thickened pyloric muscle right at birth.

- Acquired pyloric stenosis, or acquired hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, is often observed a couple of weeks after birth, when the baby begins to display the first signs of the condition (1).

Pediatric experts believe that pyloric stenosis is often acquired than congenital (2) (3). Specific factors seem to increase the risk of a baby developing an acquired or congenital pyloric stenosis.

What Are The Risk Factors For Pyloric Stenosis In Infants?

The following conditions and scenarios increase the chances of a baby developing pyloric stenosis:

- Age: Pyloric stenosis mostly affects infants in the age group of a few weeks old to six months (4). Peak incidence is seen among babies three to five weeks old.

- Hereditary: If a parent had pyloric stenosis, then the baby has a 20% higher chance of developing the condition. Hereditary pyloric happens as faulty and abnormal genes are transmitted through generations. Since genetic tests have become available widely, ask your doctor, if you want professional help in this direction.

- Gender: Baby boys are four times more likely to develop pyloric stenosis than baby girls (5). However, it is not known how gender influences the thickening of the pylorus.

- First-born baby: They have a higher incidence of pyloric stenosis though the exact reason is unknown.

- Preterm infants: They are susceptible to a host of complications, and pyloric stenosis is one of them.

- Smoking during pregnancy: Women who smoke during pregnancy are more likely to have a baby with pyloric stenosis.

- Exposure to erythromycin: Babies who are administered the antibiotic erythromycin during the first two weeks of life are at a higher risk of developing infantile pyloric stenosis. Other high-risk cases of infants developing the condition are when mothers consume erythromycin during the last couple of weeks of pregnancy or during the first month of lactation (6) (7).

- Ethnicity: According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), pyloric stenosis is common among Caucasians (white people of European descent), and less common in Hispanics and Africans. It is rare among the infants of Asian origin (8) (9).

These factors only elevate the risk of pyloric stenosis, and may not necessarily cause the disease. If a baby ticks any of the above checkboxes, then parents need to be extra careful. You can identify pyloric stenosis through its signs.

What Are The Symptoms Of Pyloric Stenosis In Infants?

The thickening of the pylorus muscle leads to several pathophysiological problems that lead to the following symptoms (10):

- Projectile vomiting: It is a unique symptom, and one of the early signs of pyloric stenosis that directly points towards the disease. The baby will throw up with force, spurting the contents of the stomach in a projectile arc flow. The vomiting is so forceful that the ejected contents could land several feet away. Projectile vomiting happens a few minutes to an hour after a feed. At this stage, the baby seems in no apparent discomfort and appears quite calm. The caveat here is that pyloric stenosis can also be present without projectile quality of the vomiting, especially at the early stages, making it difficult even for your pediatrician to be sure. The trick is repeated visit to the same pediatrician over a length of time for them to pick at the early possible opportunity, if they get serial assessment opportunities.

- Constant hunger: The baby is always hungry and demands a feed. He vomits the feed again, gets hungry, and the cycle continues.

- Waves or ripples around the stomach: You may notice a ripple or a wave-like movement run from the left to the right end of the baby’s abdomen immediately after he eats. The movement is called peristalsis, and is performed by smooth muscles of the stomach to transfer food to the small intestine. Since the pylorus is choked, the muscles use extra force to push the food. This brute thrust of the muscles is externally visible as ripples or waves on the torso around the abdominal cavity.

- Constipation: There will be fewer soiled diapers and the excreta will only be mucus or bile that originates from the intestines.

- Abdominal pain: The baby would have constant pain in the stomach, which would make him cry while rubbing his belly.

- Lethargy and dehydration: As the condition becomes acute, the baby becomes lethargic and weak. It points towards dehydration due to poor diet and metabolic alkalosis where the blood pH levels rise. Alkalosis occurs due to the loss of hydrochloric acid from the stomach through vomiting. It also causes loss of potassium electrolytes from the body (11).

Projectile vomiting alone should be a reason for alarm, but if you spot any of the other symptoms, rush the baby to a doctor right away as the condition could lead to some serious complications.

What Are The Complications Of Untreated Pyloric Stenosis?

Leaving the condition untreated can lead to the following complications:

- As the baby always vomits, his body never gets any nutrition from the food he eats. It results in a slow growth rate and drastic weight loss.

- Poor nutrition leads to a delay in the achievement of various cognitive and physical growth skills. The infant can lag behind the babies of his age.

- Repetitive vomiting irritates the stomach lining and causes tiny wounds that bleed. As a result, the baby can have blood in his vomit.

- Rarely, pyloric stenosis may cause an increase in bilirubin levels in the body, which eventually causes jaundice.

Complications can be avoided if the baby is taken for a diagnosis immediately.

How Is Pyloric Stenosis Diagnosed In Babies?

The doctor will first check with the parents about the presence of symptoms such as projectile vomiting and peristalsis waves. If these symptoms exist, then the next step is to diagnose the issue using the following procedures (12):

- Physical examination: The doctor checks for a lumpy mass of thickened pylorus on the right side of the infant’s abdomen. It would feel like an olive beneath the skin, and hence it is also called an ‘olive’.

- Test feed: The mother is asked to feed the baby at the doctor’s clinic. If the baby throws up with projectile vomiting soon after feeding or an hour later, it strengthens the diagnosis.

- Blood test: The test is for metabolic alkalosis and the count of potassium and sodium levels that determine dehydration due to acute pyloric stenosis.

- Abdominal ultrasound: During an ultrasound, the doctor analyses the thickness of the pyloric muscle to determine stenosis. An ultrasound measurement of 0.18cm and above of the pyloric muscle usually indicates pyloric stenosis. Severe cases can cause a thickness as high as 0.86cm (13). The doctor even checks real-time images of the stomach and the intestine to observe the signs.

- Barium X-ray: X-ray is seldom needed since ultrasound is sufficient to detect the condition. However, if the ultrasound test is inconclusive, as in the case of with mild pyloric stenosis, the doctor performs a barium X-ray test. In this test, the baby is fed a barium compound, which makes gastrointestinal organs visible in an X-ray. Multiple X-ray images are produced to spot a mushroom shape (mushroom sign) or shoulder shape (shoulder sign) of the pylorus, which indicates pyloric stenosis.

- Based on the severity of the condition indicated by the thickness of pylorus mass, the doctor would suggest the treatment procedure (14).

How Is Pyloric Stenosis Treated In Babies?

A minor surgery is the only way of curing the condition.

1. Restoring the electrolyte balance:

A baby with pyloric stenosis is bound to be weak and dehydrated. Therefore, he is administered intravenous (IV) electrolyte solution to address malnutrition, dehydration, and alkalosis. IV fluids are given through a drip for 24-48 hours at the hospital before the surgery.

2. Pyloric stenosis pyloromyotomy:

The surgical procedure for pyloric stenosis is called pyloromyotomy. It is either performed laparoscopically, i.e., through a small hole in the abdomen or an open incision. Most surgeons perform the laparoscopic procedure since it is less invasive and ensures better recovery after surgery.

The baby is given general anesthesia. A small slit is made above the baby’s navel to perform the surgery. No tissue is removed in the procedure, and the doctor cuts the outer layer of the pylorus to allow the muscle to bulge. Since the muscle has room to move, it relaxes, letting the stomach empty the contents. The procedure lasts about 30 minutes. Babies may have to stay in the hospital for up to three days for observation and recovery.

Post-surgical care is crucial to pyloric stenosis treatment, and parents are educated about it before the baby is discharged.

How To Manage Pyloric Stenosis In Babies After A Surgery?

The post-operative care involves several steps and scenarios. Here are some salient points:

- Vomiting will continue for some time: The infant will continue to vomit for up to three days after surgery. It is normal as the stomach is getting used to releasing the contents into the intestine and not the esophagus. Nevertheless, the vomiting is infrequent and less forceful than earlier.

- Feeding can be resumed within 24 hours after surgery: Depending on the baby’s general health, the doctor may recommend feeding within two to six hours after surgery. Only breast milk/formula and electrolyte solutions are given initially. As stated, it is normal for the baby to vomit so do not worry. You can gradually increase the feed by the third day.

- Once home, feed as usual: Older infants who eat solid food can first eat purees and liquid foods. Solid food can be introduced gradually.

- Pain-killers and antacid may be prescribed: The surgery site would feel sore and painful for several days. Therefore, the doctor may prescribe acetaminophen (16) (paracetamol) for a couple of weeks after surgery. And, antacid could be prescribed to alleviate the vomiting.

The baby will be right on track with his health within a week after surgery. But the surgery site still requires a lot of care.

How Can Parents Take Care Of The Surgery Stitches?

Keep in mind the following points to ensure the surgery site isn’t infected.

- Keep the area dry: It is essential to keep the stitches aerated to expedite the healing process. Do not bathe your baby until the incision heals and consult the doctor before bathing him for the first time post surgery. You can sponge-clean the baby, but ensure that the area around the incision is dry. Do not remove the surgical tape on the incision even when they appear to peel (17).

- Follow-up hospital visit is vital: Take the baby to the doctor a week or ten days after the surgery. The doctor reviews the scar, removes the surgical tape, and updates you on the healing progress.

- Continue to care for the incision site: Until the incision site has healed completely after the stitches are gone and tape has been removed, you must ensure that it is free of infections and is well taken care of. The incision seldom leaves a prominent scar.

Surgery, usually cures the problem, but in rare cases there could be some complications.

What Are The Probable Complications After Surgery?

Rush the baby to a doctor right away if you spot the following symptoms:

- Redness and inflammation around the stitches

- Swelling of any part of the abdominal cavity

- Baby seems to be in pain despite pain relief medication

- Projectile vomiting beyond three days posts surgery

- Pus, blood, or a clear liquid oozing from the incision

- Fever with temperature greater than 100.4°F (38°C)

- The doctor can address the above symptoms.

How Can You Minimize The Risk Of Pyloric Stenosis In Infants?

As the condition occurs spontaneously and the reasons behind the condition are unknown, it cannot be prevented. However, you can minimize the risk. Do remember that a pregnant mother smoking or taking erythromycin during pregnancy or a month into birthing, can lead to pyloric stenosis in the baby? Hence, it is best to avoid them, and thus minimize the risk.

Also, have scheduled baby checkups with the pediatrician. If the baby falls in any of the risk factor groups – baby boy, first-born, etc., then ensure you have regular doctor visits. Timely detection ensures there is less suffering and a speedy recovery.

Just in case you have any other queries, in the next section we help answer them.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How common is pyloric stenosis?

One in every 300-500 babies develops the condition within the first six months of life (18). However, it is easily diagnosable in a routine checkup session by the pediatrician before severe symptoms emerge.

2. Is pyloromyotomy treatment effective in the long run?

Yes, the baby can continue to have a healthy life and grow normally, after surgery. There are no long-term effects of the condition.

3. Can a baby suffer from pyloric stenosis again in the future?

This rarely happens. Less than 1% infants who undergo the treatment develop the condition again (19).

4. How to differentiate between GERD and pyloric stenosis?

Gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD occurs when the baby’s upper esophageal sphincter allows stomach contents to flow all the way to the mouth. The condition has similar symptoms to pyloric stenosis but has different reasons and prognosis. Here is how you can differentiate them:

| GERD | Pyloric stenosis |

|---|---|

| Regular vomiting | Projectile vomiting |

| Normal stools | Constipation and mucus-laden stools |

| Can happen within days after birth | Develops three to six weeks after birth |

| Fluctuates in intensity | Intensity increases over a period |

Pyloric stenosis could affect growth. But, the symptoms are explicit from the moment they emerge. Treatment has an excellent success rate, and the condition rarely recurs. Babies once treated from pyloric stenosis can have regular and normal meals, ultimately growing up strong like how healthy babies do!

Do you have any tips that mitigate the risks of pyloric stenosis? If yes, then leave them in the comments section below!

Read full bio of Rohit Garoo